As we continue our series on transition management, we want to try our best to tackle one of the most common questions we get on this topic: when should a transition actually start trading? Much of this is driven by the goals and deadlines of the individual client. However, even with constraints, a client (and perhaps their consultant) and the transition manager often have some near-term flexibility to decide on the day and time of the event.

What Day Should You Begin a Transition?

Let’s first approach the initial trade date itself. The main speed bumps occur with the letters of direction that need to go out to legacy managers to either terminate them or inform them that a partial reallocation is coming. Concurrently, a letter of direction must be sent to the custodian that holds the accounts in question. During the first meeting with all relevant parties, the transition manager should advise the client on the timing of the first available day for trading, based on all the necessary paperwork, the client’s goals, and operational feasibility at the custodian level.

Typically, from a big-picture perspective, clients that want to move assets from a legacy manager to a new strategy with a new manager have carefully considered the future and how to position their assets for success. Therefore, any delay from the time of that decision to the implementation of the corresponding trades results in opportunity cost risk. For that reason, clients are often inclined to select the first available day to trade during those discovery discussions.

However, I’ll offer an old adage: just because you can, doesn’t mean you should. The first available day is usually the prudent course of action, but other considerations may point to a different plan. For example, trading during earnings weeks can be a double-edged sword. It can bring important additional volume to names if a portfolio has many illiquid positions. It can also bring volatility, creating the potential for wild swings in performance. We have seen many transitions executed during earnings weeks for the additional volume, but the potential benefit should outweigh the risk. We have also seen events negatively impacted overnight due to earnings. If the first available day to trade happens to fall during an earnings week, it is a good idea to discuss this. Depending on the portfolio and the client’s level of risk tolerance, the transition start date may need to be moved accordingly. Beyond earnings, holidays with the potential to affect volumes and other days with macro-level news announcements should be factored into the decision.

Operationally, the client may also need to define the exact timing of when assets will be transferred to a new manager so the performance clock starts on an agreed-upon date. There are times when the plan for reallocation is there, but there are paperwork delays with the target manager. In other instances, the custodian might need time to set up countries for an international account for the target manager. In these cases, starting early could lead to a transitioned portfolio sitting dormant in a transition account, with no place to move the assets.

Sometimes a transition manager operates as if they are playing a game of Tetris, trying to make all the pieces fit together as seamlessly as possible. In many ways, this is just as important as the trading itself. We can help clients sift through all the variables to determine which start date offers the best chance of success.

What Time Should You Begin a Transition?

Once the initial meetings have been conducted and a start date has been selected, the client and transition manager must determine the best time to start trading. This is a fairly complicated topic, but for our purposes, let’s say the goal is to start trading as soon as possible (so starting with market-on-close orders is out the window) and that implementation shortfall versus a certain preselected time will be the strike for performance (eliminating approaches like VWAP as well). The truth of the matter is that starting too early in the day can unnecessarily inflate costs.

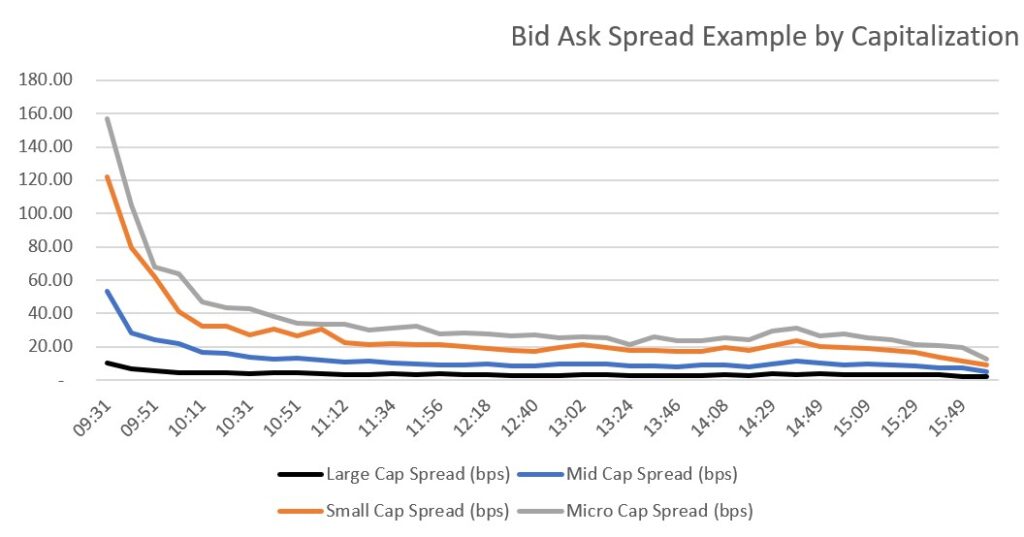

To illustrate this, let’s examine an implicit cost that is almost explicit in nature: the bid-ask spread. To be clear, we cannot estimate this cost with precision, unlike commissions and fees, which we nearly can. The cost within the spread can vary based on timing, real-time performance, the other parties involved, and the approach to execution. But what we do know is that based on the time of the day, you can help or hurt your cause.

This chart shows the pain of executing too early in the day. To make my point, I took a day in August and then made four lists of positions in 50 top stocks apiece – one each for large-caps, mid-caps, small-caps, and micro-caps. Then I took a snapshot of the bid and offer at multiple times throughout the day. The chart shows in basis points the full spreads at those times for the 50 stocks in each category.

Large-caps are clearly the kiddie slide of the bunch – spreads are higher for only the first few minutes after the open, so it doesn’t take much waiting to secure lower costs. For those adventurous types, the micro-cap slide awaits. Not only is it steep – it also takes longer to dissipate. If you start a micro-cap event early and try to lock a lot of your executions at that time, you will have over 100 basis points of options within the spread where you can execute, and most of those are unlikely to be favorable. Having to cross the full spread to execute at that time will be painful. For these events, it’s not a matter of waiting mere minutes – you’ll likely want to delay by an hour or more.

Of course, you cannot wait forever. The longer you wait, the more opportunity cost risk can work against you, so you need to strike a balance.

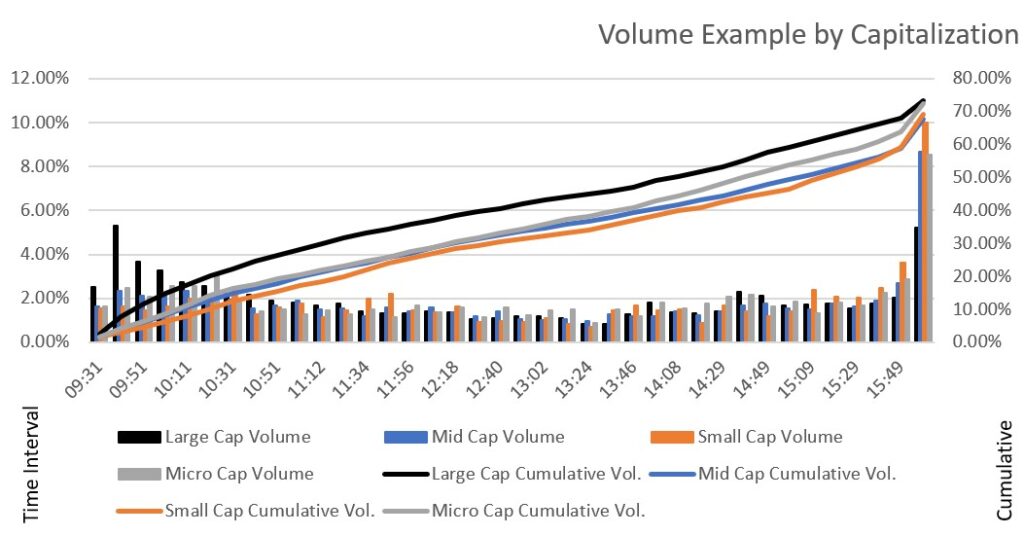

A transition manager should weigh the volume they choose to skip against the spread savings potentially captured by waiting. Using the same names on the same day, this chart depicts volumes per time interval, as well as the cumulative volume lines for each capitalization. Since spreads are not actively negotiated at or after the close, the chart ends one minute before the close. Of the four buckets of positions, the large-caps saw some decent volume early in the day relative to the others, supporting the idea of starting to trade these stocks soon after the open. For the others, you could lose 12-16% of the volume by waiting an hour to start. If the portfolio has a significant number of illiquid names, this becomes a factor. If the positions are mostly liquid, it affords the transition manager more flexibility to wait, execute at better spreads, and then worry about all the other aspects that can also drive risk and cost. For a transition manager, this is all a normal day on the job.

For your next transition event, remember that determining when trading begins – both the date and the time – is absolutely crucial.